February 11, 2018

February 11, 2018

Transfiguration Sunday

Today we read the story that is usually referred to as the Transfiguration of Jesus. What does it mean to be transfigured? A quick check of the online etymology dictionary https://www.etymonline.com/word/transfigure tells us that it comes from Latin transfigurare “to change the shape of.” It is derived from the familiar prefix trans, meaning “across” or “beyond” plus the verb figurare “to form or fashion.” To transfigure, then, is to change something or someone beyond what it was into something new and better.

As we just heard, when Jesus and his friends went up the mountain, he looked like an ordinary guy. But for some reason, he suddenly started glowing. Our reading today from Mark simply notes that his clothes became more dazzlingly white than any bleach could make them. The parallel reading in Matthew 17 remarks that his face shone like the sun and his clothes were like white light; and the version in Luke 9 says, “the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became as bright as a flash of lightning” [NIV]. Not only that, but two other men—whom Peter, James, and John somehow identify as Moses and Elijah—suddenly “appeared in glorious splendor, talking with Jesus.”

We are never quite told what all this transfiguring means. I suppose that this vision of Jesus, Moses, and Elijah is meant to suggest something about eternal life, since Elijah didn’t exactly die but was taken up to heaven in some combination of whirlwind and fiery chariot; and no one was with Moses when he died except God. In the end, we are like Peter, whose suggestion that he, James, and John should put up some kind of shelter to honor the three is dismissed by the narrator, helpfully pointing out that Peter didn’t know what he was talking about.

I’m not sure that we always know what we’re talking about, either, when we try to talk about God, or even who we are as a church.

There is a motto on the front window of our building. Anybody know what it says?

That’s right – “Inclusive, Creative, Working for Peace and Justice.” This is what we say about ourselves to the world outside our doors—or, at least, to that portion of the world that walks by our building on the way to and from the Metro.

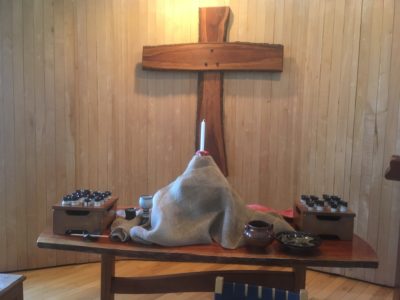

As a church, we pay a lot of attention to the “working for peace and justice” part. Every Sunday at Circle Time, someone offers a prayer as they light the Peace and Justice candle. We give a large portion of our budget to organizations that work for social justice; many sermons are preached about how we can help make our society more peaceful and more just; we care deeply about racial reconciliation, about immigration, about the problems and opportunities of people who are poor, disadvantaged, or marginalized in other ways. We believe that Jesus cared about those who were powerless in his time and place, that God continues to have what some have called a “preferential option for the poor,” and we do our best as a congregation to act on that belief.

We pay some attention—but not quite as much—to the “creative” part. Celebration Circle puts a lot of time and energy into writing new liturgies and creating new visual settings for worship every season; the musicians in our midst continually enlarge our repertoire of songs and hymns; Sandra looks for artists and visual projects to enliven the gallery; our Sunday School teachers and those who offer the Word for the Children constantly look for new ways to engage the imaginations of our youngest members; Learners and Teachers is always on the lookout for new ways to encounter God and one another in classes in the School for Christian Growth; and a lot of us are artists of one kind or another. But only a very, very tiny part of our budget goes to supporting arts organizations, and we rarely stop to think about the very real ways in which the arts can transform—dare I say “transfigure”—society. Since that’s what I do in my day job, I guess that’s partly my fault. Hmmm….maybe I should offer a class in the School for Christian Growth….ok, moving right along…

So what about the “inclusive” part of our motto? We are inclusive in lots of ways. Over the years, this congregation has become less white, less gender-normative, less uniformly affluent, and less uniformly well-educated. While we are still a fairly similar bunch by many measures, these are good things, evidence of our commitment to inclusivity.

Other measures of inclusivity include the reality that everyone in the community is welcome to preach, both men and women lead worship as well as take on other leadership roles according to their gifts rather than some predefined idea of gender-appropriate activity, and any adult member can become a Steward with the proper preparation. While we still haven’t completely come to terms with how to talk about gender fluidity, we are committed to welcoming whoever walks in the door and learning about how they want to be addressed. Indeed, we’ve come a long way since our call was amended to say, “We desire and welcome participation in Seekers Church of women and men of every race and sexual orientation.”

Lately, however, we’ve had a number of preachers either apologize for referring to God as “he,” explain why they unapologetically do so, or not even seem to notice that this might be a problem. Along with that, I’ve been hearing a number of complaints about the loss of inclusive language as a shared value at Seekers and the damage that is doing to all of us, especially the children.

When Sonya Dyer and Fred Taylor gathered a few like-minded people to form Seekers Church in 1976, liturgical renewal and feminist principles were at the heart of how they envisioned our life together. You’ve heard Marjory tell the story of arriving at Seekers in those early days, and how she wept when she first saw Sonya stand at the table with Fred to offer Communion because she had never seen a woman do that before. When I arrived in 1990, the twin notions of inclusive language and gender equality were still hot topics. When hymns were introduced during Circle Time or announced during worship, we were often instructed how to change the words so that both male and female pronouns were used for God as well as for human beings. Of course, sometimes we forgot, and sometimes a lyric or two became unintentionally funny, but we were very careful about how we named God as well as how we spoke about human beings.

Why do you suppose we did that? And why haven’t we been doing it much lately?

Before we go any farther down that road, let me ask you a different question. Who does God look like? Or maybe I should ask, who looks like God? Let’s begin at the beginning.

In Genesis (not one of the readings for today) we are told that God determined to make human beings in the divine image. As the old, familiar language puts it: “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness … So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them.” [NIV]

Listen again, this time to the way that the Inclusive Bible puts it, “Let us make humankind in our image, to be like us….Humankind was created as God’s reflection: in the divine image God created them, female and male God made them.”

As I read each of these versions, did you notice any subtle change to your inner image of God? What about your inner idea of who might be “in the image of God”?

Here’s what happens for me. When I hear that God made “mankind in his own image,” I see a male God and a lot of men who look more or less like him. Since I am female, I am not part of that very masculine “mankind.” As a woman, I do not see myself as an image of this resolutely male God, even if somehow “male and female he created them.”

If, on the other hand, God speaks of making “humankind in our image” I am already included, both because God is already plural—already an “us”—and because humankind includes all genders. When I hear this translation, I do not have to perform mental gymnastics to know that I, like all humans, am a reflection of the divine image.

Unfortunately, our culture is steeped in images of a God who looks like a man. While the Eastern branch of Christianity wisely decided that we shouldn’t make pictures of the First Person of the Trinity, the West went on its merry way portraying the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as two men and a bird.

Indeed, more often than not, even that feathery Holy Spirit gets masculine pronouns, at least in English. Which is a bit odd, historically. As most of you probably know, ruach is the Hebrew word that most often gets translated as “spirit.” What you may not know is that ruach is grammatically feminine, as is shekinah, which is another word associated with the spirit of God in the Hebrew scriptures.

When we get to the New Testament, the Greek word for spirit is pneuma. While pneuma isn’t feminine, it isn’t masculine, either. It’s grammatically neuter—having no gender at all. So how did we get to an all-male Trinity? I don’t know how it happened, actually, but I can guess that it has something to do with unconscious bias as scripture was translated from one language to another and no one noticed what happened.

Over the years, Seekers has made many efforts to notice and to correct this unconscious bias. From the beginning, liturgies were written that spoke of God in expansive, creative, poetic terms. After years of attempting to change the old language on the fly, in 1996, at Pat’s urging, we adopted the New Century Hymnal to replace the Pilgrim and United Methodist Hymnals which we had been using. While some of the lyrics are a bit clunky, this was a worthy effort by the United Church of Christ to offer some new hymns and some new words to old hymns that were less sexist and more inclusive than anything that was previously available. And, of course, many of us try to lead by example, hoping that others of you will notice that when our only image of God is “Father,” we limit our understanding of God’s illimitable reality, as well as the ability of many adults and children to find themselves in God.

In an essay titled “Why Inclusive Language Is Still Important” Jann Aldredge-Clanton recounts a story that she attributes to Judith Liro, pastor of St Hildegard’s Community in Austin, TX:

Several factories are built on a river, and they pollute the water of a village downstream. A hospital is built to treat the illnesses that result, but there is still a need to track down the source of the pollution, to stop the pollution, and to clean up the water itself. Many organizations including the Church do the important work of the hospital. Yet I have also come to realize that the Church is one of the factories that contribute to the problem. Our liturgical language with its current, heavily masculine content supports a patriarchal hierarchical ordering. Most are simply unaware of the power of language. The status quo that includes the exploitation of the earth, poverty, racism, sexism, heterosexism, militarism. . . is held in place by a deep symbolic imbalance, and we are unwitting participants in it. [https://eewc.com/inclusive-language-still-important/]

Wait! — What? — Weren’t we just talking about inclusive language? How did we get back to working for peace and justice?

It’s easy, really. Words matter. Images matter. When the words that we use for God put patriarchal, hierarchical, sexist images in our minds and the minds of our children, we perpetuate a world in which men and boys can imagine themselves like God, and see women and girls as lesser beings. That imagination leads directly to the hurt and suffering that is behind #metoo and #timesup, as well as to the structural racism, sexism, and all the other isms that we at Seekers hope to transfigure into the loving, caring, egalitarian realm of God.

When Peter saw Jesus transfigured into a divine being that radiated light and moved beyond time and space, he was so surprised that he didn’t know what he was saying. I invite you to join me in paying attention to what we are saying about God and about ourselves. Using creative, inclusive language to talk about God is an integral part of our work for peace and for justice. Together, we can transfigure our inner images so that each one of us—male, female, gay, straight, trans, bi, gender-fluid, and all the colors of the rainbow—can say “me too” and “you too” also. I am created in the image of God, and so are each one of you.